A Summer of Song in Estonia

Tallinn’s Song Festival Grounds, filled with a choir of thousands during Estonia’s Song Festival. This grand cultural gathering, known as Laulupidu, unites roughly 30,000 singers performing to crowds of 80,000 in the open-air arena. Early July 2025 finds Estonia’s capital alive with music and movement, as the XXVIII Song Celebration and XXI Dance Celebration – affectionately titled “Iseoma” (“Kinship”) – sweep across the city. Every five years, Estonia bursts into song and dance like nowhere else on Earth, and this year is no exception. Choirs in colorful folk costumes parade through Tallinn’s streets, and massed dancers whirl in unison on the stadium field. It’s a festival that feels like a national reunion. Families, friends, and even diaspora Estonians from abroad have flocked home to join in the celebration, underscoring the event’s aptly chosen “Kinship” theme. But Estonia is not alone in this tradition – all three Baltic countries share a passion for song and dance festivals that has defined their national identity for over a century. These summer festivals in Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania are more than mere entertainment; they are a living repository of Baltic culture and a symbol of unity, resilience, and freedom.

A Shared Tradition Born in the 19th Century

The roots of the Baltic song and dance celebrations reach back to the 1800s, when the idea of mass choral festivals swept through Europe. The concept first took hold in Switzerland and Germany, then found fertile ground in the Baltic provinces of the Russian Empire. Inspired by German singing societies, Estonia held its first national Song Festival in 1869 in the university town of Tartu. Just a few years later, in 1873, Latvians organized their inaugural Dziesmu svētki (Song Festival) in Riga. These early festivals were a revelation: hundreds of amateur singers from villages and towns singing in unison, often in their native languages, at a time when those languages had little official standing. In what is now Lithuania, strict Tsarist Russification delayed such a festival until after World War I – but once independent, Lithuania held its first Dainų šventė (Song Celebration) in 1924 in Kaunas. Despite this staggered start, all three nations embraced the concept of large-scale folk singing and dancing as a means to celebrate and preserve their culture.

.avif)

.avif)

Crucially, these festivals emerged during the Baltic national awakenings – social movements that nurtured local language, folklore, and identity under imperial rule. In Estonia, for example, the 1869 Laulupidu was organized by national activists like Johann Voldemar Jannsen as a showcase of Estonian-language music and pride. Latvians similarly saw their 1873 festival as a statement of cultural self-confidence in a Baltic German-dominated society. Choirs learned folk songs and newly composed choral pieces that drew on folk melodies. As decades passed, the festivals grew in scale and popularity. Mixed choirs joined the initially all-male lineups, and by the early 20th century these song celebrations had become high points of cultural life in Estonia and Latvia.

In Lithuania, the path was a bit different. Under Russian rule, the Lithuanian language had even been banned from public print for 40 years. Yet folk singing traditions quietly persisted in villages and among Lithuania’s minor communities (in areas under Prussian rule). After independence in 1918, Lithuania quickly caught up: the 1924 Song Festival in Kaunas drew choirs from across the new republic and established a tradition that continued through the 1930s. By the eve of World War II, each Baltic nation had cemented the Song Festival as a national celebration of folk culture, a ritual where singing in one’s own language was an expression of nationhood.

Keeping the Flame Through War and Oppression

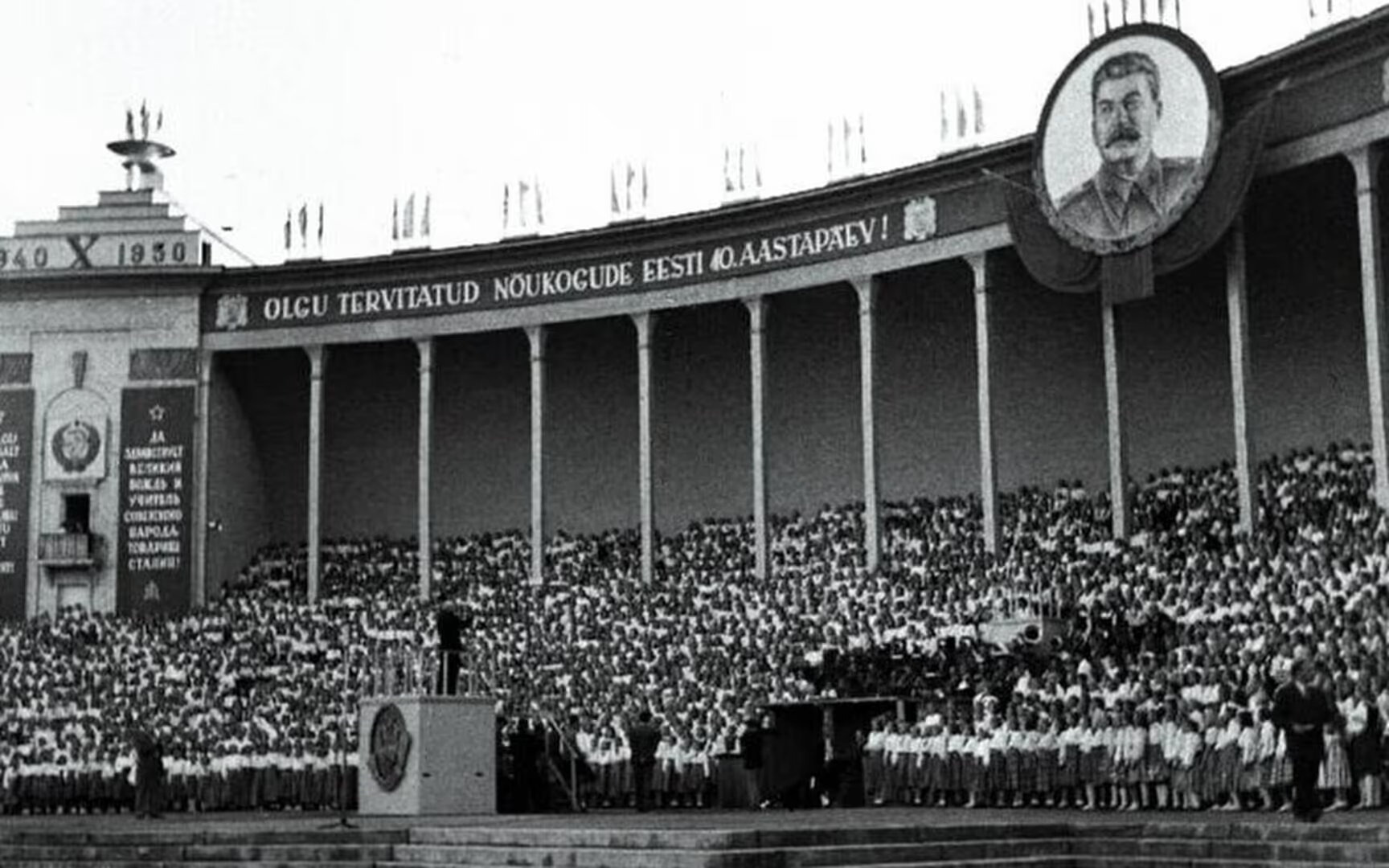

The joyous singing was soon interrupted by turmoil. The Soviet and Nazi occupations during World War II silenced the festivals for a time (Latvia’s festivals paused during the wars, and Estonia’s scheduled 1942 festival was canceled due to the war). However, once the Baltics fell under Soviet rule after the war, an intriguing dynamic emerged. The Soviet authorities decided to allow the song and dance festivals to continue, seeing them as useful outlets for “folk” expression – albeit under close control and with a heavy dose of propaganda. In Estonia, the Song Festival was revived in 1947 in Tallinn, now as an officially sanctioned Soviet event. Similarly, Latvia re-established its national festival by the late 1940s, adding a large folk dance component in 1948 to create the full Song and Dance Festival format it has today. Lithuania’s festivals resumed in the 1950s under Soviet auspices.

Yet even as Moscow’s regime co-opted these traditions, they became a subtle form of cultural resistance. Soviet occupation authorities mandated that certain songs be included – mass choirs were required to sing odes to Lenin and Stalin, the Communist Party, and the official anthems of the USSR and the Soviet republics. Folk song lyrics were scrutinized for political subtext. Overtly patriotic or religious tunes were struck from the programs. For example, in Latvia a beloved choral work “Gaismas Pils” (“Castle of Light”), which speaks about the rebirth of a free Latvian nation, was excluded from some Soviet-era festivals due to its symbolism. Every festival had to open with the Soviet anthem and close with “The Internationale.” Nonetheless, tens of thousands of Estonians, Latvians, and Lithuanians still came dressed in traditional folk costumes and singing in their mother tongues – a quiet act of defiance in itself. As one participant later recalled, “We sang what they asked us to, but we sang our songs even louder.”

.avif)

The authorities could not stop the emotional power of certain pieces. In Estonia, a song called “Mu isamaa on minu arm” (“My Fatherland is My Love”) became an unofficial anthem during Soviet times. Though not banned outright, its passionate patriotic message resonated deeply. Crowds would often demand it as an encore at the Song Festivals, standing and shedding tears as it was performed. These gatherings, ostensibly apolitical folklore events, thus nurtured the embers of national consciousness year after year. By the 1980s, each festival attracted around 30,000 performers and huge audiences – remarkable numbers in countries of only a few million people. The Soviet-run festivals inadvertently sustained the very national spirit that the regime had tried to extinguish.

.avif)

Singing Revolution: When Songs Became a Weapon

In the late 1980s, the repressed flames of Baltic nationalism burst into open fire – and song became a weapon of peaceful revolution. This period, aptly dubbed the “Singing Revolution,” saw all three Baltic nations push for independence from the Soviet Union through mass, music-fuelled demonstrations. The term was coined by artist Heinz Valk after witnessing 200,000 Estonians spontaneously singing patriotic songs at the Tallinn Song Festival Grounds one night in June 1988. “A nation who makes its revolution by singing and smiling should be a sublime example to all,” Valk wrote, marveling at the sight.

.avif)

Indeed, by summer 1988 the “ice of Soviet censorship was broken” – singers at public rallies dared to revive the once-forbidden national anthems of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Audiences waved old national flags that had been banned for decades. In Estonia, massive song rallies erupted: crowds gathered night after night at the Song Festival Grounds, singing everything from folk tunes to rock anthems of the moment. In neighboring Latvia and Lithuania, similar scenes played out as music became the heartbeat of the Atmoda (Awakening) and Sąjūdis movements.

One iconic moment of Baltic unity came on August 23, 1989. On that day – the 50th anniversary of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact that had doomed their independence – about two million people joined hands in a human chain stretching over 600 kilometers from Tallinn to Riga to Vilnius. This peaceful protest, known as the Baltic Way, was accompanied by song. A specially written trilingual song, “The Baltics Are Waking Up” (sung in Estonian, Latvian, and Lithuanian) blared from loudspeakers as people linked arms across borders. The lyrics hailed the three Baltic sisters standing together to defend their rights. It became a smash hit of the revolution, powerfully symbolizing the kinship of the three nations in their quest for freedom.

During these years, songs old and new were the soundtrack of political change. Crowds sang folk hymns that their great-grandparents had sung, as well as new rock ballads calling for liberty. Even when Soviet tanks rolled in to attempt a crackdown in early 1991, protesters met them not with violence but by singing in the streets. In Lithuania, as Soviet troops stormed the Vilnius TV tower in January 1991, people knelt and sang the folk song “Žemėj Lietuvos” in defiance, even as bullets flew. The Lithuanian president Vytautas Landsbergis urged citizens: “Look into the eyes of the soldiers…and sing. Song has helped us for many centuries…let’s not pay attention to that shooting, let’s sing!”. In the end, the singing nations triumphed without firing a shot – by September 1991, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania had regained their independence. The world had witnessed a unique revolution where choirs of ordinary people stood down an empire. As a contemporary observer noted, the Balts had proven that “spiritual power can overcome military power”.

Freedom in Chorus: The Festivals Today

When the Baltics finally emerged from the Soviet shadow, their cherished song and dance festivals were free to return to their original glory. After 1990, the festivals in each country restored their pre-war names, symbols, and repertoire. For the first time in half a century, the national flags flew openly at the song arenas, and the national anthems could ring out without fear. In Latvia, the 1990 Song Festival famously included exiled Latvian choirs from abroad and culminated with the entire audience of 100,000 singing “Dievs, svētī Latviju” – the Latvian national anthem – together, a song that had been forbidden for decades. One journalist described the atmosphere as a “back to the future” homecoming, as diaspora Latvians and locals joined voices in freedom. A similar catharsis occurred in Estonia and Lithuania’s first post-independence festivals, where old patriotic songs once suppressed by the Soviets became highlights of the program. The song festivals had fulfilled their ultimate historical mission: they had helped these nations sing themselves free.

.avif)

Three decades on, the tradition is not only alive and well – it’s positively flourishing. The Song and Dance Celebrations of the Baltics have earned recognition from UNESCO as part of the Masterpieces of Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity. They are unique in the world for their scale and level of public participation. Typically held every five years (Estonia, Latvia) or four years (Lithuania), each festival is a massive undertaking that involves years of regional choral competitions and rehearsals to select the best groups. By the numbers, these events are staggering: recent festivals in Latvia have featured over 40,000 performers – including choirs, orchestras, and dance troupes – all performing as volunteers out of love of tradition. In 2018, celebrating Latvia’s centenary, the festival culminated with a choir of 16,000 singers on stage and an audience of 67,000 filling the Mežaparks amphitheater in Riga. That week-long festival saw around 500,000 people attend various events, roughly a quarter of the entire population of Latvia. Estonia’s 2019 Song Festival (the 150th anniversary edition) likewise hit record numbers – tickets sold out as 60,000 spectators plus 35,000 singers packed the Tallinn festival grounds, prompting organizers to pause ticket sales for safety reasons. And in Lithuania, the Song Celebration remains a revered national ritual, drawing participants from across the country and the global Lithuanian diaspora. The festival is regarded as a “unique manifestation of national culture and a symbol of unity and strength” for Lithuania, sentiments equally true in the other Baltic states.

%20(1).avif)

Latvian Dance Festival performance in 2018. Thousands of folk dancers form intricate patterns on the stadium field, moving in unison to music. The dance celebration is an integral part of the Baltic festival tradition, added in the mid-20th century to showcase folk choreography alongside songs. While choir singers fill one venue, parallel mass dance performances take place in a large arena, featuring row upon row of dancers in traditional dress swirling to polkas and waltzes. The sight is mesmerizing – imagine over 10,000 dancers performing a coordinated suite of dances, creating human mosaics that tell the stories of agrarian life, seasons, and folklore. In Estonia, the dance festival (Tantsupidu) usually kicks off the festivities, with multiple shows at Tallinn’s Kalev Stadium where spectators watch giant folk dances that sometimes involve props like hoops, flags, or even farm tools. Latvia and Lithuania’s dance performances are equally grand, paying homage to each nation’s regional folk costumes and choreographic styles. These dances are not professional ballet – they are performed by amateurs: students, office workers, grandmothers and grandchildren alike – all united by heritage. The sheer enthusiasm and precision on display underscore how deeply rooted folk dancing remains in Baltic culture. Together, the singing and dancing at these festivals present a vibrant panorama of national traditions, lovingly preserved and passed down through generations.

.avif)

United by Song: One Baltic Voice

Despite each having their own language and songs, Estonians, Latvians and Lithuanians see their song and dance festivals as something that profoundly unites the Baltic peoples. All three countries have walked a similar historical path – from national awakening in the 19th century, through the trials of foreign domination in the 20th, to freedom regained in 1991 – and through it all, singing and dancing kept their spirits alive. It’s little wonder that during the independence struggle, they were called the “singing nations.” To this day, a popular saying in the region goes, “Latvians are born singing, Estonians are born singing, Lithuanians are born singing.” The festivals also foster camaraderie across borders. Choirs from one Baltic country often perform at the others’ celebrations as honored guests. There have even been special joint concerts, such as a Baltic Unity Song Festival held in 2018 where choirs from all three sang together in each other’s languages.

In essence, the Song and Dance Celebrations serve as a powerful reminder that although Estonians, Latvians, and Lithuanians have distinct cultures, their love of collective song is a common thread stitching the Baltics together. The tradition’s inclusion on UNESCO’s heritage list in 2008 recognized this shared cultural treasure. Visiting any of the festivals is an emotional experience – many spectators, even foreigners, speak of being moved to tears by the beauty of tens of thousands of voices singing as one. For Baltic people, the festivals are often described as almost spiritual. They are moments when the entire nation seems to breathe in unison through song. Children who learn folk songs in school join youth choirs, who later join adult choirs, keeping the cycle unbroken. Grandparents dance alongside teenagers. Heritage isn’t just on display; it’s lived, felt, and sung from the heart.

As the sun sets on Tallinn this week in July 2025, one can easily imagine the scene: a massive choir under the arched stage of the Song Festival Grounds begins the beloved finale, “Mu isamaa, mu õnn ja rõõm” – the national anthem of Estonia. Thousands in the audience rise, many with tears welling up. Similar scenes will have played out in Latvia’s and Lithuania’s own festivals, past and future, each note echoing the struggles and triumphs of these nations. In that powerful moment, history and the present merge. The Baltic peoples once sang for their freedom, and every time they gather in jubilation to sing again, they remember that freedom – like a song – is something you must keep voicing and sharing to truly remain alive.

.png)

.png)

.png)